- Receding waters during an extreme drought revealed a 3,400-year-old city along the Tigris River.

- Iraq has been experiencing climate change-induced drought for months.

- Archaeologists are rushing to preserve artifacts exposed or destroyed by climate change.

A severe drought brought on by climate change revealed an ancient Bronze Age city in Iraq, and gave archaeologists a chance to map it, researchers announced Monday.

The drought hit the region in December, prompting locals to draw large amounts of water from a reservoir on the Tigris River, in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, to prevent crops from drying out. The lower water levels resurfaced ancient structures from a 3,400-year-old city along the river.

Iraq is the fifth most vulnerable country to climate change in the world, according to the United Nations. Warming temperatures have made the country drier and prone to drought, threatening agriculture and the livelihoods of those who live there. "Water reserves are far lower than what we had last year, by about 50 percent," a senior adviser at Iraq's water resources ministry told AFP in April. The advisor attributed the concerning situation to "the successive years of drought: 2020, 2021 and 2022."

Researchers have long known of the city's remains, but can only investigate them when they periodically resurface during droughts. They last emerged during a dry spell in 2018, and researchers aren't certain when they'll be back.

In January and February, a team of Kurdish and German archaeologists frantically rushed to the archaeological site — called Kemune — to excavate and map most of the city, which includes a palace with 20-foot-tall walls, several towers, and multistory buildings.

Archaeologists say the city dates back to the time of the Empire of Mittani, a kingdom which controlled large parts of northern Mesopotamia and Syria between 1550 and 1350 BC. A large earthquake destroyed the Mittani city around 1350 BC, causing the upper parts of the walls to come crashing down on buildings and burying them. Experts say being buried beneath the fallen walls might have helped preserve the ancient structures after years of being submerged underwater.

"The excavation results show that the site was an important center in the Mittani Empire," Hasan Ahmed Qasim, an archaeologist, chairman of the Kurdistan Archaeology Organization, and a lead of the excavation team, said in a statement.

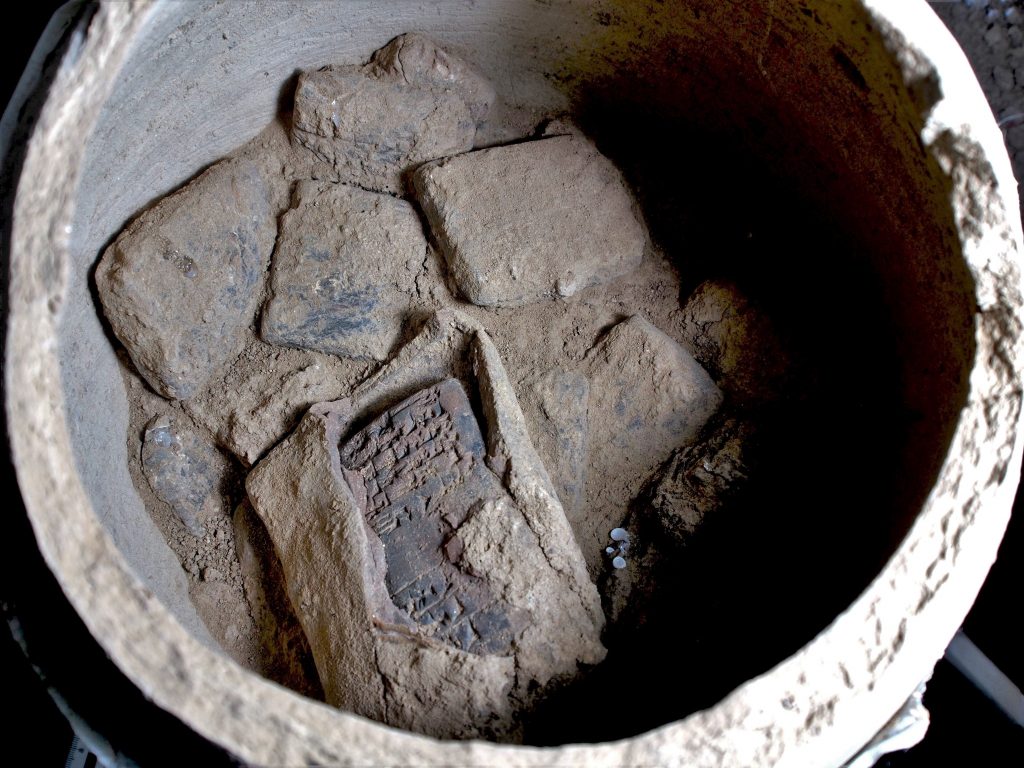

Researchers also discovered five ceramic jars with more than 100 cuneiform tablets, or slabs of writing used during the early Bronze Age — including one tablet still in its original clay envelope. The tablets date back to just before the earthquake destroyed the city.

"It is close to a miracle that cuneiform tablets made of unfired clay survived so many decades underwater," Peter Pfälzner of the University of Tübingen, who was also part of the excavation team, said in a statement.

The ancient city is now completely underwater. According to a press release, upon finishing up their excavation in February, the archeologists covered the site with plastic sheets to prevent further deterioration when the city, once again, became submerged.

The team is not the only group of researchers rushing to preserve artifacts being exposed or destroyed by the effects of climate change. Receding waters, melting glaciers, and rising sea levels are unearthing — and sometimes damaging — new finds. For instance, in Nevada's Lake Mead, long-submerged bodies have cropped up due to receding water levels. In Hawaii, ancestral remains, which are traditionally buried along the shore, are under threat from coastal erosion and rising seas.

"Encroaching seas are eroding those burials out and human remains are going to continue to be exposed," Jennifer Byrnes, a forensic anthropologist, told Insider in May.